The psychology of grief: modern theories of loss, change and grief

Grief is one of life’s most disorienting experiences. Whether you’re navigating the loss of a loved one, a relationship, your health, a dream, or even a version of yourself, grief shows up in layers. The world no longer makes sense and we are lost and in pain.

Over the years, several psychological theories have emerged to help us make sense of grief. These models aren’t meant to box our experience of grief – they’re maps, not mandates. They offer language, structure, and insight for the terrain of loss. In this post, I’ll give an overview of five widely respected theories, including a way to view grief and loss as part of the natural life cycle. In further posts I’ll explore these in more detail and distill them into practical tools you can actually use to support your healing.

1. Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief

As discussed in the previous post, the Five Stages of Grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – were introduced by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross to describe the emotional journey of those facing terminal illness. Over time, the model evolved to encompass anyone experiencing loss. These stages are not fixed checkpoints or a checklist to complete, and people may revisit stages multiple times or skip some entirely. Denial can feel like shock or numbness. Anger may arise at the unfairness of the loss. Bargaining might involve “what if” or “if only” thoughts. Depression can show up as profound sadness. Acceptance means recognising the reality of the loss and learning how to live alongside it.

How to use this in practice: Try keeping track of what you are feeling and rating the intensity. Notice which emotions are present each day without judgment. This kind of simple reflection tool builds emotional awareness and helps normalise the shifting waves of grief.

2. Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement

Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut introduced the idea of a dual process within grief. Those who have suffered loss tend to oscillate between:

- Loss-oriented activities (feeling the grief, remembering the loved one, acknowledging the pain)

- Restoration-oriented activities (managing life changes, building new routines, stepping into a new identity)

Both activities are valid. Both are part of grieving. Loss-oriented coping involves directly engaging with the emotional pain: tears, reminiscing, longing, even anger or guilt. Restoration-oriented coping is about adjusting to the new reality: finding support, establishing new routines, and discovering who you are now. The key insight is that we naturally oscillate between these two, and that is normal.

How to use this in practice: Build a rhythm into your week that allows for both sides. Set aside time for grief, then consciously shift into restoration. You’re not “escaping” grief when you do this; you’re actively doing the work of dealing with the past, the present, and the future.

3. Worden’s Tasks of Mourning

J. William Worden’s theory views grief as a series of four tasks, empowering people to be active participants in their healing (I will be exploring these more in the next post). These tasks are not necessarily linear, but each represents a key part of adapting to life after loss.

- Accept the reality of the loss – This means moving from “This can’t be real” to “This is real” – even if that truth feels unbearable.

- Work through the pain of grief – Rather than avoid, repress, or minimise your feelings, you allow them to surface and move through you.

- Adjust to a world without the deceased – This may include changes in identity, routines, roles, or even spirituality.

- Find an enduring connection while moving forward – The goal is not to forget but to hold the relationship in a new, meaningful way.

How to use this in practice: Approach each task as a gentle prompt. Ask yourself, “What am I avoiding right now?” or “How has my role changed since the loss?” These tasks, done with intention, can provide a roadmap that can help grief feel less overwhelming and more manageable.

4. Continuing Bonds Theory

For decades, the conventional wisdom was that healthy grieving meant letting go, or moving on. The Continuing Bonds Theory, proposed by Klass, Silverman, and Nickman, suggests that people don’t stop relating to those they’ve lost – they continue those bonds in new, transformed ways. Instead of severing ties, you build a different kind of connection. This might mean continuing to feel the person’s presence, seeing them in your dreams, or continuing their legacy. These bonds can provide comfort, stability, continuity, and even guidance. The grief remains part of your life, but it becomes integrated, not dominant.

How to use this in practice: Allow yourself to start a “Connection Practice” with the person you’ve lost. Write them letters. Carry something that reminds you of them. This isn’t about staying stuck in the past – it’s about honouring the enduring impact that this person has had on your life.

Grief is not a detour from life – it is life.

5. Meaning Reconstruction Model

Robert Neimeyer’s Meaning Reconstruction theory sees grief as more than emotional pain – it’s a profound crisis of meaning. When we experience a significant loss, the assumptions we hold about life, purpose, and even our identity can crumble. We ask, “Why did this happen?”, or “Who am I without them?”, or “How can this happen?”. The path to healing, then, lies in reconstructing meaning – not just around the loss, but around the self, and about how life works in general. This model recognises that humans are story-makers. Grief disrupts our inner narrative. Healing involves forming new stories that include the loss, not exclude it. Meaning-making doesn’t erase the pain, but it helps it feel less senseless.

How to use this in practice: Use narrative tools to make sense of your grief. Try prompts like:

- “How has this loss changed me?”

- “What meaning am I making from this experience?”

- “How do I want to incorporate this loss into my life?”

So, which model of grief is “best”?

The truth is, whichever you find most useful.

Each of these theories offers a different lens – and grief rarely fits one neat path. You might find comfort in the five stages theory when emotions feel chaotic, or in Worden’s tasks when you need a sense of agency. Continuing Bonds could help when you fear forgetting. Meaning Reconstruction might help to guide you in picking up the pieces when everything in your world feels shattered. Just work with what makes sense to you in the moment.

Bringing it all together: navigating life changes

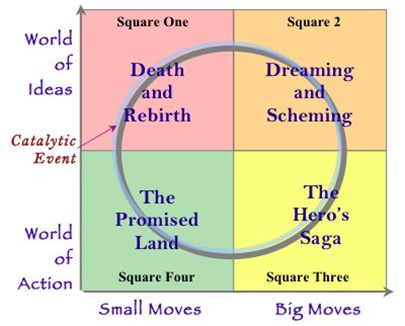

Sometimes it helps to view grief as part of the wider life cycle. Martha Beck, an American life coach and sociologist, offers a framework that maps the human journey of loss and regeneration in four distinct stages (see previous post). By offering a broader perspective, this theory offers a context in which to understand grief as a natural response to the cycles of change we all have to navigate.

Square 1: Death and Rebirth

This is where we start. This is the stage of loss, where life falls apart – or at least feels like it does. Something we depended on – an identity, a relationship, a person, a job, a belief – has ended or is ending. Square 1 is marked by confusion, denial, and disorientation (as in Kubler-Ross’s model). This is where we do the grief work, and where the above models can be useful. In this phase, it’s tempting to rush ahead, to patch things up quickly or “get back to normal.” But Beck invites us to do the opposite: to rest, to grieve, to listen. This is the season of the inner winter. But it is not the end of the story.

Square 1 mantra: “I don’t know what the hell is going on, and that’s okay”

Martha Beck pairs each stage of the Change Cycle with a mantra – short, grounding phrases that reflect the emotional and psychological essence of that phase. This mantra normalizes the chaos, confusion, the unravelling, the sense of ‘lostness’ that often accompanies change. It gives us permission to not have it all figured out. Instead of rushing to fix things, we are invited to sit with the unknown and trust that clarity will come in its own time. This is a mantra of surrender – and survival.

Square 2: Dreaming and Scheming

When we have done the work of accepting the loss (Warden’s first and second tasks), but there is no clear new path yet in place, Square 2 is where imagination begins to spark. This is where we ask the questions that Neimeyer suggests: How has this loss changed me? Who am I now? What meaning can I make of this? This is the time to dream, to play with ideas, to follow curious nudges and whispers. We might not know how things will unfold – and that’s okay. This phase is about possibility. Beck encourages people to notice what feels light, joyful, or quietly compelling. Pay attention to those breadcrumbs. They often point toward where we’re meant to go next.

Square 2 mantra: “There are no rules, and that’s okay”

In Square 2, we step out of old systems, roles, and beliefs. It’s a liminal space, where the old map no longer applies. This mantra reminds us we get to imagine, invent, and re-create. The “rules” we used to follow might not work here – and that’s not a problem. It’s an opportunity. This is the realm of creativity, intuition, freedom, and play.

Square 3: The Hero’s Saga

Next comes action. Square 3 is where we begin turning our visions into reality. It marks the transition from primarily focusing on loss-oriented activities, to engaging more with restoration-oriented activities as in Stroebe and Shut’s Dual Process Theory. It also relates to Worden’s third task of adjusting to the new world we find ourselves in. We might be learning new skills, testing ideas, facing fears. It’s exciting – but also hard. Obstacles show up, doubts creep in, old patterns push back.

Beck calls this “The Hero’s Saga” because this is the part of the journey where courage, perseverance, and support matter most. It is a stage of trial and error. Mistakes aren’t failures – they’re feedback. This square asks us to keep going, even when the road gets bumpy. You’re building something new.

Square 3 mantra : “This is harder than I thought it would be, and that’s okay”

This is the action phase – where we build the new life we’ve imagined. And it’s often more effortful, messy, or humbling than we expected. The Square 3 mantra honours the struggle. It doesn’t sugarcoat it. But it also reassures us that difficulty doesn’t mean we’re on the wrong path. It means we’re growing, stretching, learning.

Square 4: The Promised Land

In Square 4, the new normal has arrived. Life feels aligned again. We may have come to a new sense of connection or a renegotiation of the relationship we have lost, as in the Continuing Bonds Theory, and in Worden’s fourth task. There’s peace here. But Square 4 isn’t the end of the story – it’s just a resting place. Eventually, some part of life will shift again, and the cycle will begin anew. This is simply the nature of life.

Square 4 mantra: “Things are more wonderful than I ever imagined, and that’s okay”

Square 4 brings integration, ease, and a sense of arrival. The mantra here acknowledges that we’ve not just returned to a sense of stability – we’ve been transformed in the process. This mantra isn’t naïve – it’s earned.

Beck’s model reminds us that change isn’t linear – it’s cyclical. Being aware of which stage we are in, and what to expect in each stage, helps us to normalise our experiences, and to alleviate the fear that we will be endlessly stuck in the depths of grief work.

Grief is not a detour from life – it is life

These psychological models of grief are invitations, not instructions. The most important theory? The one that helps you feel a little more understood, a little more supported, and a little less alone.

You are doing the work simply by feeling what you feel. And it will eventually shift and change. Because life is change. Trust that.